This blog is based on: Harris, R. and J. Yan (2017) Absorptive Capacity: Definition, Measurement and Importance.

Professor Richard Harris is a Co-Investigator of the Productivity Insights Network

Government industrial policy often sets out to encourage firms with high levels of productivity to locate in geographic areas (or in industrial sectors) that are underperforming – for example, to aid rebalancing and to strengthen the resilience of such areas or sectors, as well as to provide new jobs. Examples include encouraging inward investment of foreign-owned multinational firms and facilitating the creation or strengthening of ‘clusters’ of co-located firms around a core of higher productivity firms (see the UK Government’s White Paper, 2017[1]).

Firms exhibiting higher productivity (such as multinationals) tend to spend more on R&D, and thus introduce new innovative products wanted by consumers, or new production processes which are more flexible and cost efficient. And they are more likely themselves to export into highly competitive markets (and thus need to be capable of doing so). The dynamic capabilities such firms have can potentially ‘spill over’ to other less productive firms if the latter are capable of assimilating into their business this new knowledge from the external environment in which they operate. Engaging in cooperating or partnering with, and sharing information that is available from, suppliers, customers, competitors, or other specialised sources, is evidence that firms are involved in internalising new, external knowledge spilling over from more productive firms. Similarly, firms that introduce new business practices for organising procedures (e.g., business improvement methods) and/or new methods of organising work practices and/or new methods of organising external relationships and/or implementation of changes to marketing concepts or strategies, are also demonstrating their capability of being able to internalise new knowledge, methods and practices. Overall, the ability of firms to engage in such activities denotes their ‘absorptive capacity’; like the ability of an individual to learn, absorptive capacity (AC) is not just about firms being able to potentially benefit from spillovers but rather using knowledge from the external environment to improve their productivity. If a firm has a limited ability to learn, then new strategies or technology that spills over, and that can potentially help firms become more productive, are likely to have only limited impact. More generally, having too many firms with lower AC is also likely to be a major reason for lower productivity in general, as it is shown in Harris and Yan (2017) that the higher is absorptive capacity, the greater the likelihood that a firm will do R&D, innovate and export – with all three activities, key underlying drivers of a firm’s (and thus nation’s) long-run productivity.

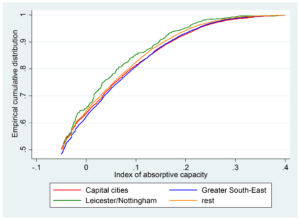

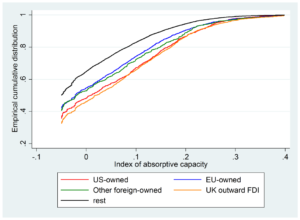

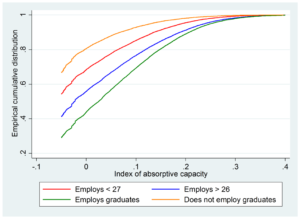

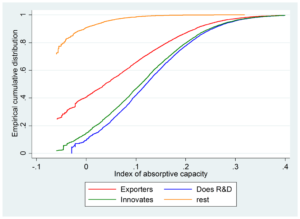

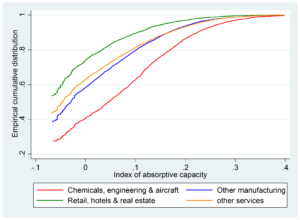

Harris and Yan (op. cit.) have used nationally representative data for Britain (based on the governments’ Community Innovation Surveys for 2004-2014) to calculate the level of absorptive capacity for each firm; from this it is possible to look at which firms have higher levels of AC. Figure 1 summarises the results; it shows the cumulative distribution (i.e., from the lowest to the highest values) of absorptive capacity separately for firms with a range of different characteristics. Establishments located in the Greater South East of England (which covers the administrative regions of the South East, Eastern England, London and the South West) generally have higher absorptive capacity throughout (their distribution lies to the right of the distributions of other areas); followed by capital cities (London plus Cardiff and Edinburgh); and then other areas (excluding Leicester and Nottingham, which have the lowest levels of absorptive capacity). The second panel shows that multinational firms are must better as well, especially establishments that belong to UK multinationals, followed by US-owned firms. Establishments employing graduates have significantly better absorptive capacity levels, as well as those that are relatively larger, innovators (product and/or process), those engaged in R&D, and to a lesser extent exporters. Establishments involved in the chemicals, engineering and aircraft sectors perform the best, followed by other manufacturing, and other services (excluding retail, hotels and real estate). When taking account of other factors that determine a firm’s AC (such as its size, age and organisational status), the differences shown in Figure 1 remain statistically significant (i.e., they are not ‘explained away’ by other underlying firm level characteristics).

The main results obtained by Harris and Yan have important lessons for policymakers, especially in terms of whether encouraging more multinationals to locate in (underperforming areas of) the UK, and pursuing a ‘clusters’ policy, will improve productivity levels. Firms with high levels of AC do have higher productivity, but the majority of less productive firms (the ‘tail’ of underperforming businesses) are more likely to benefit from their presence only if they have sufficient capacity to absorb potential spillovers from co-location.

Figure 1: (Weighted) Absorptive capacity indices by various firm characteristics, Great Britain, 2004-2014

Source: Harris and Yan, 2017 (Table 1)

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-strategy-building-a-britain-fit-for-the-future.